Common sense from (the other) down under

/The doctor who helped discover the NuXI Variant is shocked at the world’s hysterical overreaction

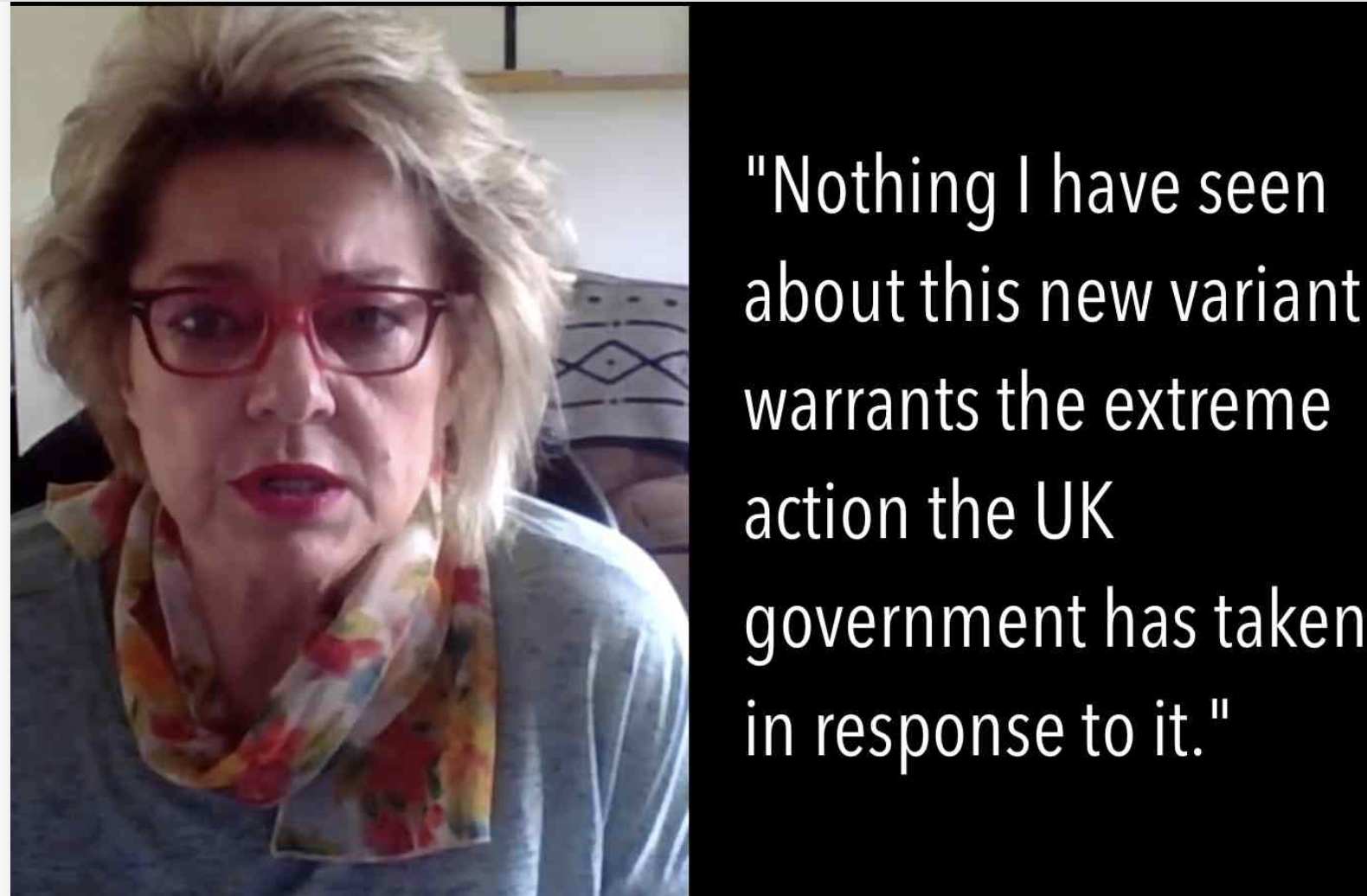

By DR ANGELIQUE COETZEE FOR THE DAILY MAIL

As chair of the South African Medical Association and a GP of 33 years' standing, I have seen a lot over my medical career.

But nothing has prepared me for the extraordinary global reaction that met my announcement this week that I had seen a young man in my surgery who had a case of Covid that turned out to be the Omicron variant.

This version of the virus had been circulating in southern Africa for some time, having been previously identified in Botswana.

But given my public-facing role, by announcing its presence in my own patient, I unwittingly brought it to global attention.

Quite simply, I have been stunned at the response – and especially from Britain.

And let me be clear: nothing I have seen about this new variant warrants the extreme action the UK government has taken in response to it.

No one here in South Africa is known to have been hospitalised with the Omicron variant, nor is anyone here believed to have fallen seriously ill with it.

Yet Britain and other European nations have reacted with heavy travel restrictions on flights from across southern Africa, as well as imposing tighter rules at home on mask-wearing, fines and extended quarantines.

The simple truth is: we don't know yet anywhere near enough about Omicron to make such judgments or to impose such policies.

In South Africa, we've retained a sense of perspective. We've had no new regulations or talk of lockdowns because we're waiting to see what the variant actually means.

We've also become accustomed here to new Covid variants emerging. So when our scientists confirmed the discovery of yet another, nobody made a huge thing of it. Many people didn't even notice.

But after Britain heard about it, the global picture started to change.

Even as our scientists tried to point out the huge gaps in the world's knowledge about this variant, European nations immediately and unilaterally banned travel from this part of the world.

Our government was understandably angered by this, pointing out that ‘Excellent science should be applauded, not punished.'

If, as some evidence suggests, Omicron turns out to be a fast-spreading virus with mostly mild symptoms for the majority of the people who catch it, that would be a useful step on the road to herd immunity.

We'll learn in the next two weeks if that's the case.

The worst situation – of course – would be a fast-spreading virus with severe infections. But that's not where we are at the moment.

Here in South Africa, what I and my GP colleagues are seeing doesn't in any way warrant the knee-jerk reaction we've seen from the UK.

For one thing, we're not – at least for now – treating patients who are severely ill.

Take my first Omicron case, the young man I mentioned earlier. It didn't occur to him that he had Covid: he thought he'd had too much sun after working outside. After he tested positive, so did his wife and four-month-old baby.

So far, the patients who've tested positive for Omicron here have been mainly young men – a mixture of vaccinated and unvaccinated (though, in our statistics, ‘unvaccinated' can also mean ‘single-vaccinated').

Only yesterday, I saw five more patients who had tested positive for the new variant. They all had a very mild illness.

So, at the moment, I'm afraid it seems to me that Britain is merely hyping up the alarm about this variant unnecessarily.

Yes, the picture might one day look different. I have yet to see older, unvaccinated people infected with the new variant, for example, and they might well present with a more severe form of the disease.

But the reality is that Covid is something we have to learn to live with. Look after yourself and get your vaccines. Above all, don't panic – and that goes for governments as well.