An important case for Greenwich home owners, and property owners everywhere

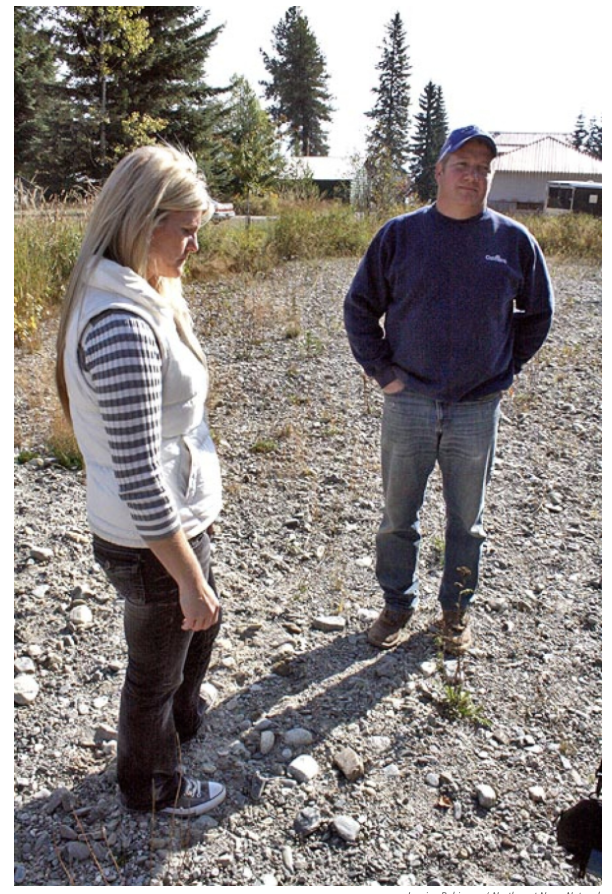

/environmental warriors, mike and Chantell Sackett on the site of their former home

Environmental(ist) catastrophe? SCOTUS takes on water

Ed Morrisey, Hot Air:

What constitutes “navigable waters”? That question has bedeviled Mike and Chantell Sackett for 15 years, and now it comes back again to the Supreme Court. Ten years ago, the Supreme Court took an incremental approach to the Waters of the United States (WOTUS) Act and the EPA’s regulation based on its jurisdiction over “navigable waters.”

With the EPA still blocking the Sacketts from building a house on their own land, a very different Supreme Court has taken the case back up again. This time, the Washington Post notes, they will likely aim higher than the Administrative Procedure Act (APA):

The justices said Monday that they will consider, probably in the term beginning in October, a long-running dispute involving an Idaho couple who already won once at the Supreme Court in an effort to build a home near Priest Lake. The Environmental Protection Agency says there are wetlands on the couple’s roughly half-acre lot, which brings it under the jurisdiction of the Clean Water Act, and thus requires a permit.

The case raises the question of the test that courts should use to determine what constitutes “waters of the United States,” which the Clean Water Act was passed to protect in 1972.

….

The ruling ten years ago clearly rebuked the EPA for its attempts to fine the Sacketts into submission and force them to demolish the house that they had already begun to build before the agency informed them of their wetlands finding. Despite the clear signal sent by the unanimous decision in 2012, the EPA has still battled the Sacketts over the use of their two-thirds acre of land with the argument that a house would somehow impair “navigable waters.” Justice Samuel Alito warned Congress to remove the ambiguities around that term and settle on a reliable definition soon:

Real relief requires Congress to do what it should have done in the first place: provide a reasonably clear rule regarding the reach of the Clean Water Act. When Congress passed the Clean Water Act in 1972, it provided that the Act covers “the waters of the United States.” 33 U. S. C. §1362(7). But Congress did not define what it meant by “the waters of the United States”; the phrase was not a term of art with a known meaning; and the words themselves are hopelessly indeterminate. Unsurprisingly, the EPA and the Army Corps of Engineers interpreted the phrase as an essentially limitless grant of authority. We rejected that boundless view, see Rapanos v. United States, 547 U. S. 715, 732–739 (2006) (plurality opinion); Solid Waste Agency of Northern Cook Cty. v. Army Corps of Engineers, 531 U. S. 159, 167–174 (2001), but the precise reach of the Act remains unclear. For 40 years, Congress has done nothing to resolve this critical ambiguity, and the EPA has not seen fit to promulgate a rule providing a clear and sufficiently limited definition of the phrase. Instead, the agency has relied on informal guidance. But far from providing clarity and predictability, the agency’s latest informal guidance advises property owners that many jurisdictional determinations concerning wetlands can only be made on a case-by-case basis by EPA field staff. See Brief for Competitive Enterprise Institute as Amicus Curiae 7–13.

Allowing aggrieved property owners to sue under the Administrative Procedure Act is better than nothing, but only clarification of the reach of the Clean Water Act can rectify the underlying problem.

Neither the EPA nor Congress has lifted a finger to provide a reliable and sufficiently determinate definition that limits EPA authority in any meaningful way. The Sacketts have spent another decade fighting the same issue even after that unanimous SCOTUS decision

….

Here’s the history of Mike and Chantell Sackett’s 15-year struggle to build on their tiny lot.

(Excerpt)

The difficulties began almost as soon as they started clearing the lot, which they had bought two years before [2007] for $23,000. EPA officials stepped in and claimed the Sacketts’ land was on a federally protected wetland, and their construction project violated the Clean Water Act. The EPA forced a halt to the work and issued a compliance order, prohibiting further construction and threatening fines of up to $75,000 per day if they failed to comply.

….

It’s worth noting that the Sacketts’ property wasn’t some untouched piece of wilderness—the lot is located in a mostly developed subdivision, with roads and other homes nearby and water and sewer hook-ups on site. Moreover, their land doesn’t drain to any other body of water, which makes the alleged Clean Water Act violation all the more baffling.

When the Sacketts attempted to contest the EPA’s ruling, it was as if they had passed through the bureaucratic looking glass: There seemed to be no rules and nothing made sense. They requested a written explanation for why the EPA had claimed authority over their land, which the agency promised but never delivered. The EPA provided them no proof of a violation and no opportunity to contest its claims of a violation.

The Sacketts did everything they could to reason with the EPA, eventually even hiring outside experts to conduct a hydrologic analysis of the property. But it was like Alice reasoning with the Red Queen, and since the EPA claimed the compliance order was not reviewable in court, the couple couldn’t even get a third party to fairly adjudicate the question of agency authority.

Unfortunately for the EPA, their behavior violated their Sacketts’ constitutional right to due process—and so, represented by the Pacific Legal Foundation, the Sacketts fought back to get their case heard in court.

In 2012, the Sacketts’ case went before the Supreme Court, and they won. The Supreme Court unanimously ruled that property owners can promptly challenge EPA claims that their lands are federally regulated wetlands and therefore may not be developed. (In a separate concurrence, Justice Samuel Alito cited a major portion of an amicus brief filed by CEI, berating the EPA for the vagueness of its wetlands definition.)