Infrastructure costs and the Green New Deal

/Jamie Diamond had something interesting to say the other day:

Dimon slammed the government's impediment of the economy.

'We have fallen into the rut of false narratives, which distracts us from facing reality.

'We don’t define our problems properly. If you have the wrong diagnosis of a problem, you will certainly have the wrong solution.

'Even if you have the right diagnosis, you still may arrive at the wrong solution — but your odds are certainly much better.

'Our policies are often incomprehensible and uncoordinated, and our policy decisions frequently have no forethought and no identification of desired outcomes.'

'Regulation has dramatically impeded our ability to build good infrastructure in a timely manner — the cost of building a highway has more than tripled in 20 years purely because of expenses due to regulations.

That echos what I’ve been squawking about for years, so I thought I’d dig up a couple of articles that illustrate the point: People demanding and expecting the creation of a massive solar and wind power infrastructure by 2035 are in for a very rude awakening. Of course, this isn’t news to the true Greens, whose goal is the impoverishment of America — they couldn’t care less whether there’s any energy to run the country, but for the millions of chumps who are so blithely going along with “the plan”, thinking that they’ll still be able to heat their homes, enjoy strawberries from Chile in December, and travel farther than ten miles from their village, things are going to really suck.

The plan started simply, as many plans do: The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority would extend one of its light rail lines from Cambridge to Boston’s northern suburbs. It was estimated to cost less than $500 million when planning began in earnest in 2005. And it would provide transit access to some of the region’s most densely populated neighborhoods that didn’t already have it.

Then things veered off track. By 2015, state lawmakers temporarily canceled the Green Line Extension (GLX) after costs had ballooned to a staggering $3 billion; progress resumed after an internal audit and management overhaul that reduced the price tag by several hundreds of millions.

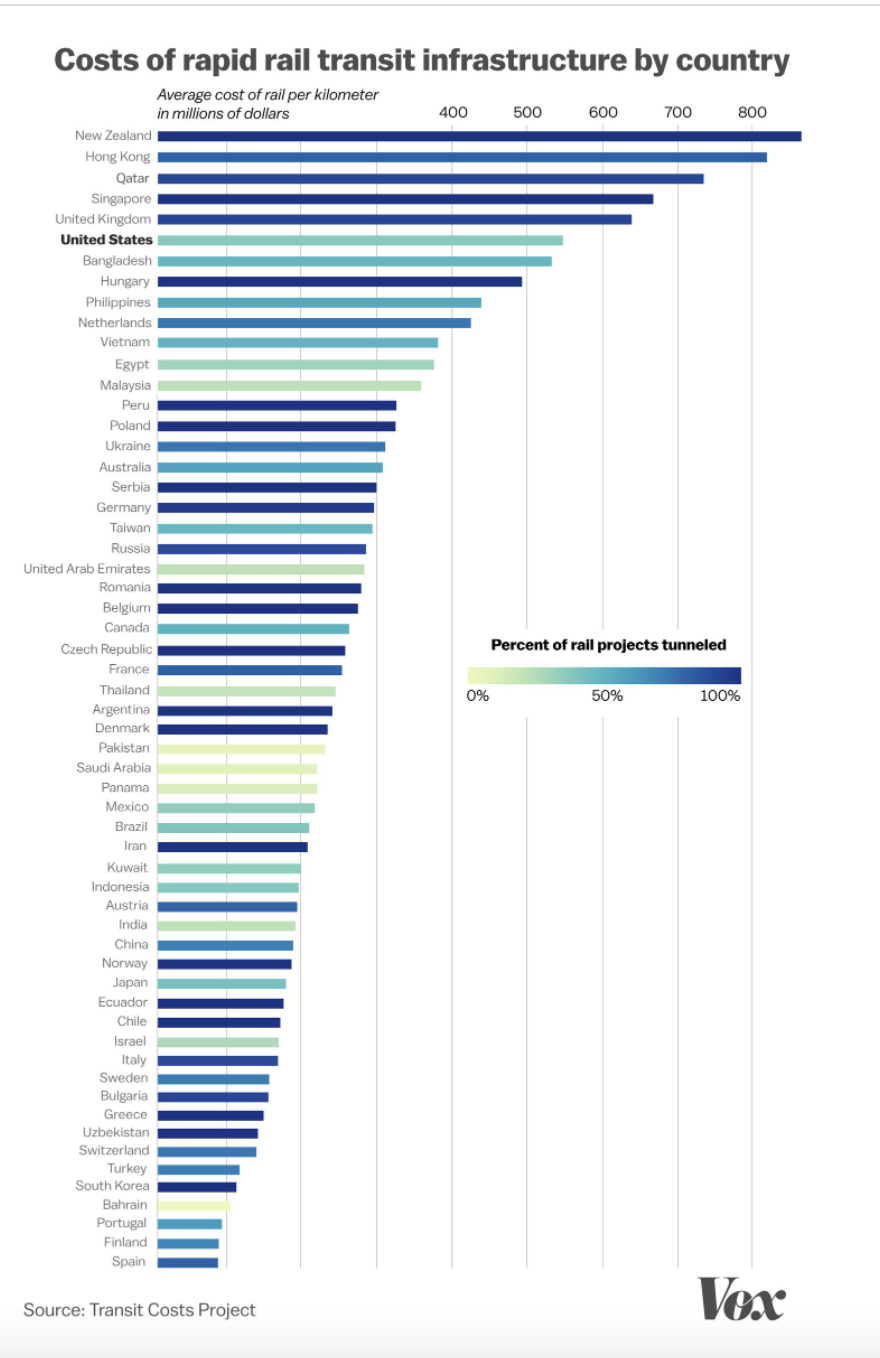

These escalating costs were not an anomaly. Mile for mile, studies show the U.S. spends more than all but five other countries in the world on public transit, and more on roads than any other country that discloses spending data.

Research doesn’t point to a single particular cause. Instead, a confluence of factors have contributed, from lack of expertise and ineffective project management, to processes for citizen input. “It’s death by a thousand paper cuts,” Goldwyn said of a case study of the Green Line Extension he led with Levy and Elif Ensari, an NYU transportation and land use research scholar.

Goldwyn and Levy have focused their research on urban rail projects because they tend to be large and distinct, whereas road projects tend to consist of numerous, smaller efforts. And with transportation generating 30% of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, mostly from private vehicles, there is an existential urgency to build more public transit.

Yet the extraordinary expense of construction is a significant barrier to that need. The first phase of the Second Avenue Subway in Manhattan, the most expensive subway project in the world, cost $2.5 billion per mile, nearly five times the cost of a similar extension in Paris.

More cost, fewer projects

The other major factor is what Brooks terms the “rise of the citizen voice.” The 1970s brought a wave of federal and state legislation (the National Environmental Policy Act being the most prominent) that gave residents and activists a greater say in public decision-making. While these new laws surely brought some benefits — particularly to project neighbors — they also added time and expense. Given that the U.S. ranks 13th in transportation infrastructure quality globally, those added costs don’t seem to have yielded better roads. “I find it hard to believe we’re building better highways than countries in western Europe,” Brooks said — or, she added, that the U.S. is taking better care of the environment.

Even Vox— Vox! Hs something to say on the subject:

Why does it cost so much to build things in America?

This is why the US can’t have nice things.

on June 28, 2021 7:00 am

I moved to Montgomery County, Maryland, in 1999. Officials had been thinking about building a rail line across the county for more than a decade at that point. More than 20 years later, the Purple Line is only 40 percent built and has run hundreds of millions of dollars over budget, according to the Washington Post.

As the Action Committee for Transit, a local pro-transit organization, documented, residents of the wealthy DC suburb of Chevy Chase have led a decades-long crusade against the light rail project, which will benefit the entire region, by claiming that a “tiny transparent invertebrate” might be at risk. “When no endangered amphipods were found,” the detractors turned to other arguments. However, repeated references to the potential harm to the Columbia Country Club and also a public comment disparaging the needs of people in less affluent communities makes clear that much of the stated concern was likely never environmental or financial.

….

Then there’s the complexity of building across multiple jurisdictions. The federal government often provides funding for a project that requires multiple cities or counties to coordinate, all to complete a multibillion-dollar project unlike one they’ve probably ever accomplished before, often without a clearly defined leader — it’s like the most dysfunctional group project ever.

Much of the above seems to have been taken from a paper by Alon Levy, so let’s look at what he has to say:

Long lead times are largely a problem of red tape. In addition to the many layers of review, infrastructure projects in the U.S. constantly face the threat of potential lawsuits — a problem shared with other countries with laws that favor litigation, like Germany, even if their costs are lower overall. Take the 1970 National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), which requires “environmental impact statements” for “major federal actions” that could “significantly affect” the environment. As the Niskanen Center’s Brink Lindsey and Samuel Hammond note in their 2020 report Faster Growth, Fairer Growth: In the early days, NEPA’s procedural requirements were modest: An EIS could be as short as 10 pages, and the legislation didn’t provide for a private right of action. Courts soon declared a private right of action, though, and under the pressure of litigation the law’s demands grew ever more onerous: Today the average EIS runs more than 600 pages, plus appendices that typically exceed 1,000 pages. The average EIS now takes 4.5 years to complete; between 2010 and 2017, four such statements were completed after delays of 17 years or more.

… [N]o ground can be broken on a project until the EIS has made it through the legal gauntlet – and this includes both federal projects and private projects that require a federal permit. Meanwhile, the far more numerous environmental assessments (the federal government performs more than 12,000 of them a year, compared to 20-something Environmental Impact Statements) have likewise become much lengthier and more time-consuming to complete. ….