While we're waiting for EOS's report on the coronation, here's an interesting article on the importance of ritual, and the role it plays in the culture of both the Zdembus of Zambia and Great Britain

/archbishop Marcus Wallaby summons the people to Westminster Abby

Food for thought, if not agreement

Sohrab Ahmari: Coronation is ritual humiliation

… Modern Britons may well ask: why do we find ourselves locked into a ritual — a religious ritual, to be precise — inherited from the ancient past? Even if some share the Christian faith that underpins rituals like the coronation, can’t they practise that faith privately, without the need for a solemn, state-sanctioned ceremony involving bishops, priests, crowns, sceptres, and holy oils? Why do we need public ritual at all?

All this is a tragedy, because old rituals like the coronation can play a deeply salutary — and even progressive — role in societies otherwise wracked by modern capitalism’s cruel, arbitrary hierarchies. We human beings do all sorts of things that have no functional value in themselves but that help us communicate symbolically. We shake hands. We exchange rings. We are wired, it seems, for ritual: a pattern of words and actions characterised by formality, rigidity, and repetition. The closest analogous human behaviour, according to many anthropologists, is children’s games.

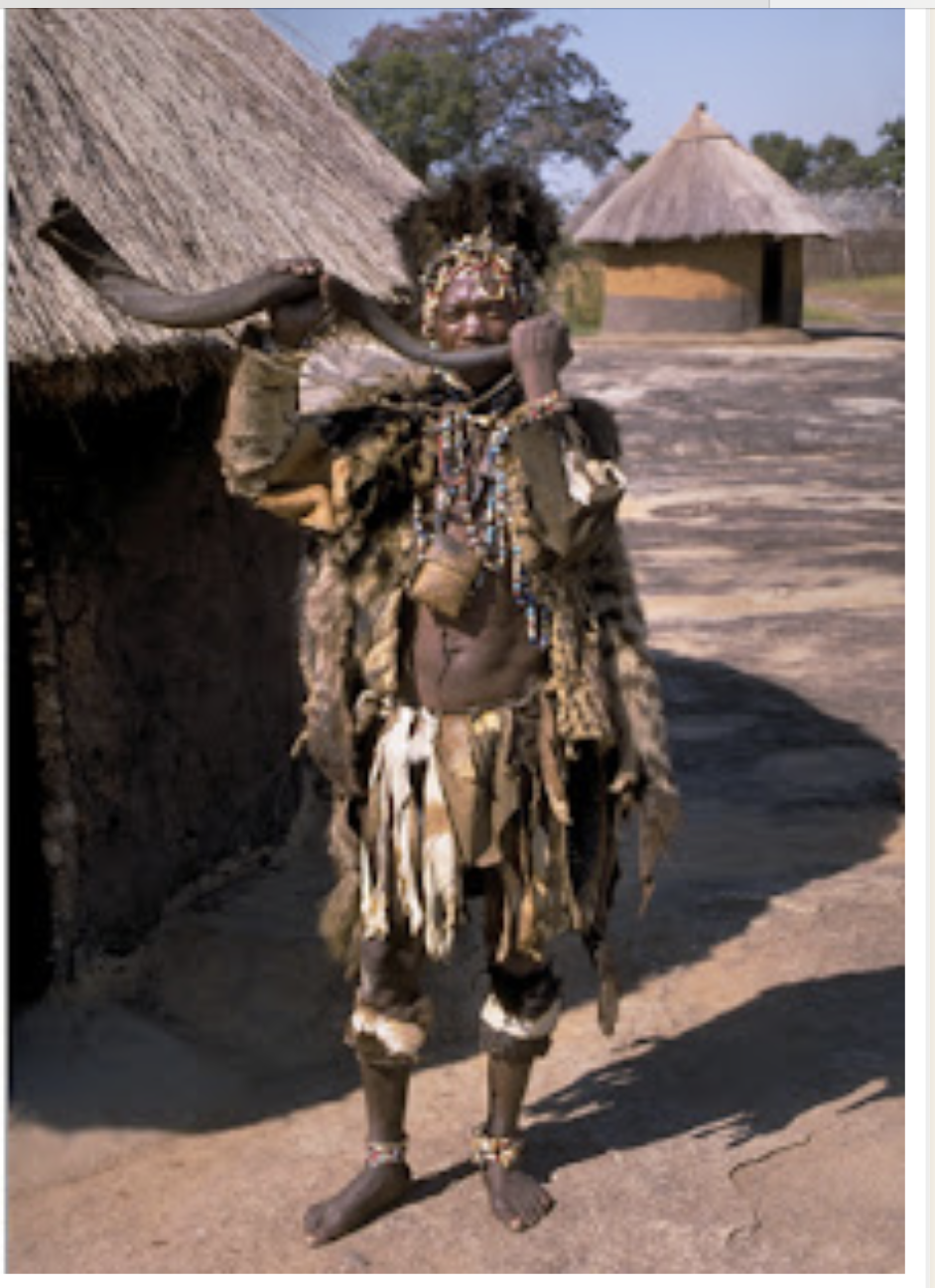

…Before he assumed power, a Ndembu chieftain had to undergo ritual humiliation at the hands of a mythic figure known as the Kafwana; coded female, she was associated with the land and the people who tilled it, those who weren’t politically or militarily strong but who nevertheless possessed a sacral power. Among other things, the chieftain-to-be had to absorb a barrage of insults and criticisms from other villagers; once installed, he didn’t dare hold it against the people. In this way, the religious ritual taught the chieftain that he was first and foremost a servant.

By humbling himself, and dispensing with his normal privileges, the one undergoing the ritual must recognises what Vic called “humankindness”: “a generic bond between men.” Without it, the hierarchical community has no qualms about excluding and even destroying the weak. Far from locking people into the past, then, ritual allows them to confront present and future challenges. Ritual, in this telling, humanises societies.

On the surface, the coronation of King Charles and Queen Camilla is about as distant as can be from the chieftainship ritual of the Ndembu people. But the rite’s underlying structures are are shockingly similar. The Anglican ceremonial adds several layers of Christian symbolism, not to mention genteel ornamentation — all of which softens the liminal humiliation of the king-to-be and his bride — but the fundamental process is the same.

First, there is the separation of the ritual subjects — Charles and Camilla — from humdrum British reality. This is marked by their carriage ride to Westminster Abbey. Next comes the liminal stage, where Charles’s face is literally covered by Anglican churchmen, using a canopy of golden cloth, known as the anointing screen. The covering shields the most sacred element of the ritual from prying eyes, but it also means that Charles is erased as an individual.

The core action of the liminal stage is the anointing of king’s hands, breast, and head with oil. In the Bible, such oils are the mark of the self-sacrificing King of Kings: Jesus is anointed before he is to undergo his passion, death, and burial. Once the screen is removed, the anointed king will kneel at the high altar while the archbishop recalls how “Our Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God … was anointed with the Oil of gladness above his fellows.” Thus Charles, as a Christian statesman, is united with the sacrifice of Christ. He is giving up something, trading his personality for that of the sovereign, dutybound to serve the commonweal.

Finally, there is Charles’s reaggregation: he re-enters society with elevated status, symbolised by the crown and sceptre. But again, this occurs only after he has ritually identified himself with society’s victims — indeed, with the anointed Victim. All this marks him out as the servant-ruler of the British people, rather than merely a king.

Today’s economic hierarchies tell the winners that they owe their status to no one and nothing but their own “meritocratic” efforts. This isn’t, in fact, true: study after study demonstrates that social mobility has stalled, especially in the Anglosphere. But it makes for particularly obnoxious elites: if they owe their status to no one, then they also have no obligations to society’s losers. Against such a backdrop, Britain’s traditional monarchic rituals, not least the coronation, are a very different, and much-needed, account of what the high owes the low.

When we glimpse the communitas lying beyond everyday structures — when we leave behind profane everyday reality to play the solemn, cosmic game of ritual — we are possessed by a vision of what society could or should look like. Here, the mighty chieftain submits to the lowly Kafwana. Here, the omnipotent Son of God consents to be humiliated. And His Majesty the King consents to follow the mortified god-man, even into the tomb.

Personally, and for myself, I’d still hang the bastids from the lampposts, but I’d also be tempted to decorate those same posts with the bodies of the “particularly obnoxious elites”. And I do appreciate one commenter’s pithy summation: “Put simply, Chesterton’s fence”.

On the other hand, if the current royal family is humble, I’ve seen no sign of it.