Global warming: is there NOTHING it can't do? (UPDATED)

/oh dear, sir, i feel a bit woozy

A dear friend, possibly my last acquaintance who still subscribes to the NYT, sends along this story; even she found it a bit … silly.

From The New York Times:

A Royal Soldier Fainted in the Heat. It Holds a Lesson for All of Us.

Even as climate change upends our lives, we seem set on doing things the way we’ve always done them.

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/12/magazine/royal-soldier-fainting-climate-change.html?smid=em-share

The article itself is behind a paywall so I haven’t read it, but the headline says it all because — duh — there’s nothing new under the sun.

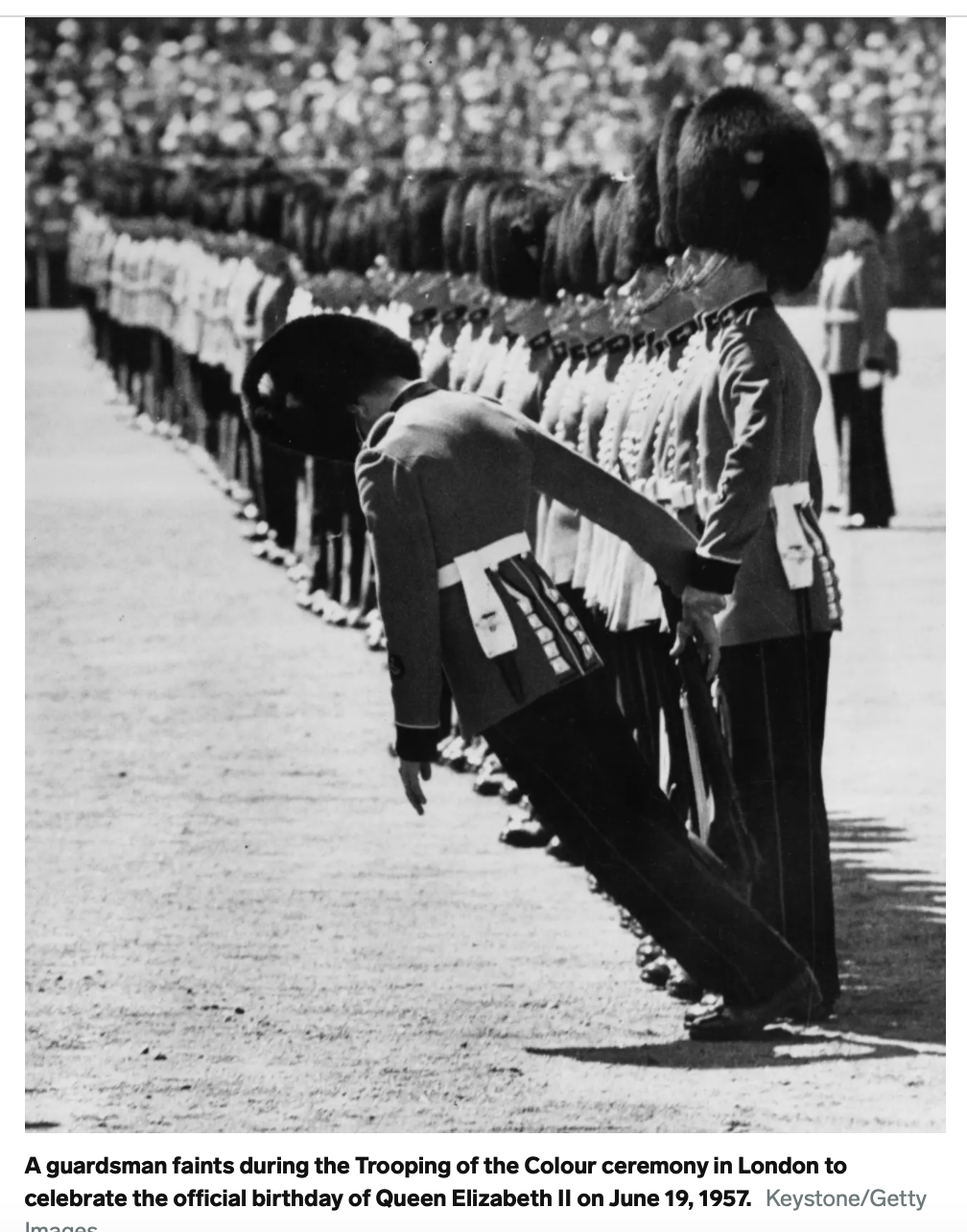

Multiple soldiers fainted at rehearsals for King Charles' birthday parade during a heat wave. Photos show it's been an issue for decades.

This has happened so frequently in the past that the Royal Guard is actually trained how to faint.

Not surprisingly, the phenomenon is not confined to British weaklings:

Journalism has been dead for a long time, but I still miss the occasional reporter who would at least consider what he was writing about, instead of just parroting the group-think of the day. And do you remember when there were editors who would clamp a lid on their idiot staff? Neither do I, but I’m told that they once existed.

UPDATE: Here’s the article, from a non-protected website. It’s exactly as bad as you’d expect. I’d suggest that it was written by a high school summer intern, but I believe the Times only hires from the best of the best of Yale graduates, so I guess it’s just a case of arrested development: Yale’s good at doing that.

…You know the Household Division. They are the stately human chess pieces guarding London’s royal palaces whom you can watch online, refusing to smile, as vacationing YouTubers pelt them with wisecracks at close range. What these soldiers do best is endure. They withstand. But that morning, London is on its way to a high of 84 degrees — 13 degrees hotter than the average high for this time of year — and the soldiers, in their thick, cumbersome hats, are performing in a shadeless gravel lot.

A trombonist goes down. One moment, he’s blaring away at the front, and the next he has fainted, prone at the others’ feet, like a crumpled bill left in front of some buskers. These soldiers are actually trained to “faint at attention” — to faint, if they must faint, with fortitude and resolve, without reaching for anything as they topple, simply falling forward like a proud, insentient tree. When the BBC camera finds the trombonist, he is on his side but still has his instrument held to his lips, his hands adhered to the horn in perfect playing position, while behind him, his colleagues play on.

Four officials in dark uniforms come to retrieve him, like stagehands fetching scenery. They carry a green military stretcher, but by the time they arrive, the trombonist is upright again. He has hoisted himself to standing by mashing the tip of his trombone’s slide into the dirt. Then, having staggered back into line, he raises the instrument to his mouth. He is joggled, woozy, but committed to expelling whatever air he’s got in his lungs into the horn, exchanging life force for music.

The stretcher people do not let him do this. They take his trombone away and walk him offscreen. But what you might have missed — what I missed the first time I watched this clip online — was that, as they scampered toward him, they momentarily crossed paths with a second group of attendants scurrying off the field. These people were also carrying a stretcher. And on their stretcher was a clarinetist. According to a news report, there were three musicians who fainted during the rehearsal — three, “at least.”

These men have names. They have identities. They have loved ones and favorite foods and dreams. I feel for them. Fainting is scary and terrible, and I feel conflicted about writing about the incident from inside my climate-controlled home.

Still, they were uniformed soldiers who volunteered to be symbols of something larger than themselves. And now, they had become symbols of something different too. We may talk of “battling” climate change, but here were actual soldiers being knocked to the ground.

This problem of overheating soldiers has arisen before. Last July, during the hottest month of the hottest year on record in England, a heat wave thrust the temperature in London to 104 degrees Fahrenheit, more than 30 degrees beyond the average high.

Airport runways and roads buckled, as did train tracks, complicating travel. (It was roughly 10 degrees hotter than the peak temperature at which Britain’s rail system was designed to function.) Computer servers couldn’t be cooled sufficiently, crashing the systems at two different hospitals; surgeries were canceled, patients turned away. Fires broke out around the city and, in a place where fewer than 5 percent of households are estimated to have air-conditioning, 664 people died.

The Household Division guards, meanwhile, roasted outside Buckingham Palace. One afternoon, the AP photographer Matt Dunham captured a regular security guard (Kevlar vest, utility belt, cuffs) pouring a drink of water into one of these soldiers’ mouths. (Drinking is prohibited while on duty.) It was a staggering image, as if a time traveler had been sent to intervene in Elizabethan times with the technology of bottled water. A dam of superhuman decorum was cracking; the heat was that unbearable. Even so, the costumed guard refused to break his posture any more than necessary. He accepted the drink with his arms locked at his sides, his bayonet-tipped rifle still propped at his clavicle. And when he tilted his head back, he did so only a few degrees, the minimum necessary for the liquid to slide inside.

What does climate change feel like, really? The core of the experience may be a sense of dislocation, of being newly and scarily mismatched to the world. It’s as if everything around us, everything we rely on, has been transported to a different place than the one it was designed for — a harsher, meaner Earth.

On Mean Earth, all kinds of previously durable infrastructure can be undermined or undone. This includes train tracks and computer servers, but also cultural infrastructure: the unexamined things we do a certain way because we’ve always done them this way, that’s why. Consequently, the predicament of that trombonist in his woolen clothes feels increasingly familiar. Kids sent to sleepaway camps where it’s too hot, or too smoky, to do much outdoors; vacationers on beaches littered with dead fish after a colossal algae bloom; homeowners rebuilding after their second wildfire or flood — all are re-enacting rituals that are slipping out of phase with their environments and thus being drained of their joy and logic.

That frenetic scene at the British parade — the uniforms, the stretchers, the scurrying, the chaos, the dignified persistence of everyone to face forward and persevere — reminded me of a war movie, with medics speedily extracting the wounded from trenches during an assault. Prince William later issued a statement which framed the incident in just that way: “Difficult conditions but you all did a really good job.” His men had withstood the attack.

UPDATE II: Surprisingly, the author, one Jon Mooallem, is a man, even though he writes — and throws, probably — like a girl. Unsurprisingly, he is a product of the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism [sic].