Poor New York: if it's not the prosecutors, it's the judges — and the state legislature

/Bronx judge who replaced lenient jurist freed 2 accused teen shooters pending trial

The Bronx judge who replaced a notoriously lenient colleague in handling juvenile cases just allowed two accused teenage shooters — including one charged with murder — to go free pending trial, The Post has learned.

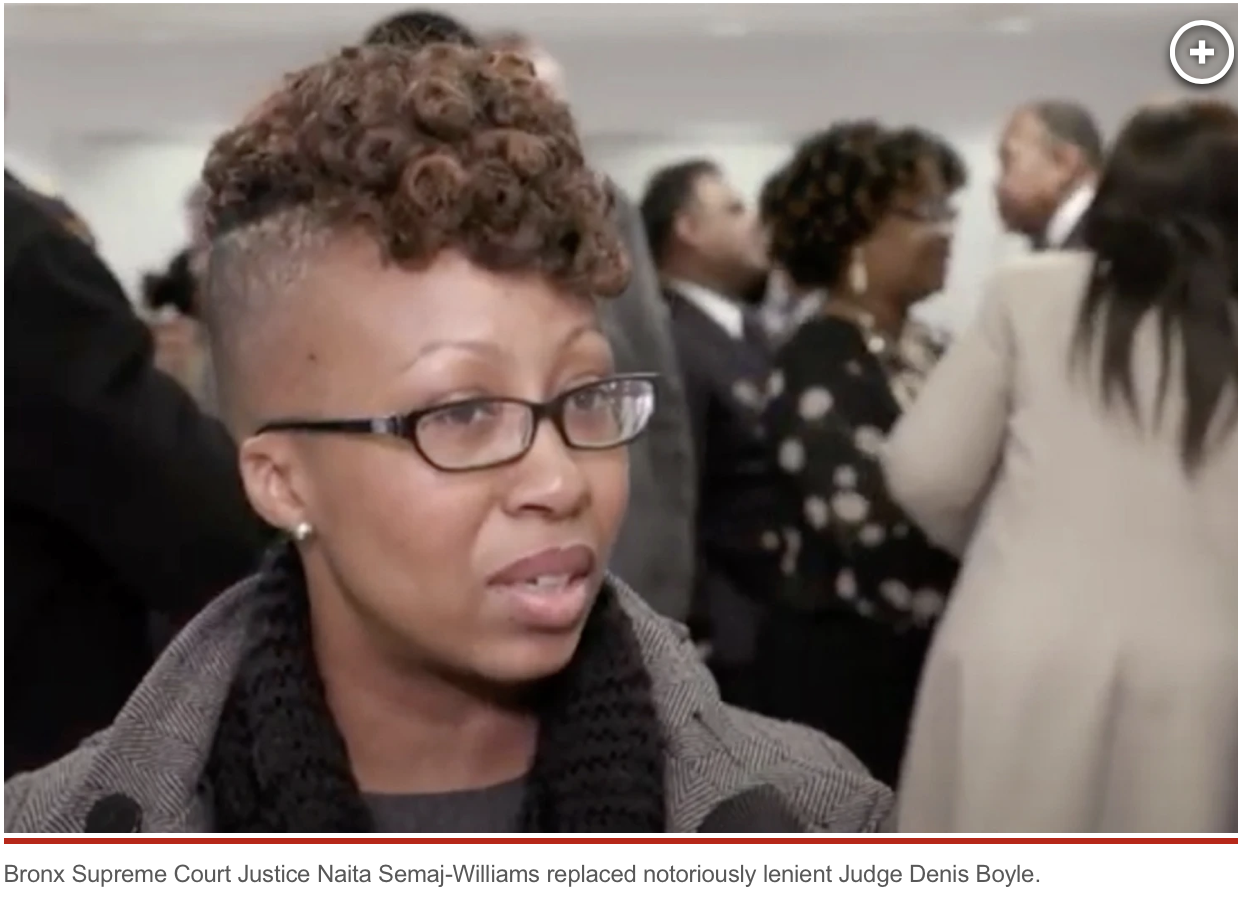

Bronx Supreme Court Justice Naita Semaj-Williams appears to already be following in the footsteps of Acting Supreme Court Justice Denis Boyle, who transferred to adult trials and hearings after he made headlines for cutting violent teens loose on bail, law enforcement sources said.

Prosecutors from the Bronx District Attorney’s Office had asked for both 17-year-old boys to be held on bail, but Semaj-Williams ruled they should be freed — one on supervised release and the other on his own recognizance — at their respective hearings on Feb. 9.

“Crime will never go down with judges like this,” a Bronx cop griped to The Post.

One of the cases involves Braulio Garcia, 17, who was arrested on Jan. 14, along with 16-year-old Jonathan Aponte, in connection with the New Year’s Day death of a good Samaritan who jumped onto Bronx subway tracks to save another man. Both have been charged with murder, manslaughter, robbery, gang assault and other crimes.

Garcia was arraigned on an indictment for second-degree murder Feb. 9 — and ordered released with supervision by Semaj-Williams, over the objection of prosecutors.

He’s expected to be sprung following a hearing Friday, after the New York City Sheriff’s Office works out the terms of his supervised release, including ankle monitoring, the DA’s office said.

In the other case, Semaj-Williams even walked back another jurist’s decision to set monetary bail.

Judge Michael John Hartofilis had ordered 17-year-old Sharif Mitchell held on $30,000 bail or $60,000 bond at his Feb. 8 arraignment in Bronx Criminal Court on attempted murder and other charges.

But at his hearing in the youth part the next day, Semaj-Williams modified those conditions, releasing Mitchell on his own recognizance despite prosecutors’ protests.

Even more damaging than the no-bail provisions in the “reform” law passed in 2019 and which the legislature just last week refused to revise is the amendment to the discovery rules, which require the prosecution to disclose the names and addresses witnesses to defendants within 15 days of an indictment.

[The opinion piece below was written in 2019, just after the law was passed; all its predictions have proved true]

Discovery is the process through which prosecutors turn over evidence so someone accused of a crime can mount a capable defense. The new laws mandate that the prosecution must reveal all its evidence within 15 days of arraignment.

Currently, discovery is required before a trial starts, which only happens in about 3% of all cases. To be sure, this measure will equip defendants with information about the evidence against them before deciding whether to take a plea bargain, and give them more time to prepare a trial defense. Ensuring that defendants are not coerced into accepting plea deals is a worthwhile goal.

But the new law goes too far, as all five borough district attorneys have testified.

One of the primary reasons why witnesses are hesitant to cooperate with an investigation is confidentiality. Brooklyn DA Eric Gonzalez explains, “if you talk to any assistant district attorney, they will tell you that one of the first questions they are asked by victims and witnesses is: ‘Will the defendant know who I am?’ ‘Will they know where I live?’ ”

Prosecutors will no longer be able to assure witnesses that their identity will be protected, even in the case of grand jury testimony, which the new law will now require be disclosed.

Manhattan DA Cy Vance put it this way: “Having to hand defendants a roster of who has spoken out against them just 15 days after their first appearance, absent a protective order, is a seismic change that undoubtedly will dissuade witnesses who live in all neighborhoods from reporting crime.”

It gets worse. The new law increases the likelihood of defendants being granted access to the locations — stores, bank vaults, bedrooms — where they are accused of committing crimes. In a section entitled, “Order to grant access to premises,” the law stipulates that the defense may apply for “access to an area or place relevant to the case in order to inspect, photograph, or measure same.” A judge can exercise discretion about access, but the provision appears to establish a presumption of material necessity for “preparation of the case” by the defense.

Acting Queens DA John Ryan asks, “How do we tell a burglary complainant that the defendant may have the right to come into her house with an investigator to take pictures?” Beyond taking pictures, the law seems to permit the defendant to “inspect” the premises, presumably to undertake his own investigation of the crime scene. Thus a suspected home invader and rapist could be permitted to poke around the same room where he committed his crimes.