This has been one of my pet peeves for about 50 years

/How to Be a Real Anti-Racist: Teach Black Kids to Read. I’d add, we could help save the nation if we’d teach all kids to read, but this would be a start.

Kay Hymowitz, City Journal

…. I’ve been … watching “antiracism” teaching—some might call it Critical Race Theory (CRT) or social justice—take over the American education world with Omicron-like speed. Lesson plans, books, tips for in-class activities, discussion points, and curricula swamp the teachers’ corner of the Internet. The proposals come from a metastasizing number of pedagogic entrepreneurs and activist groups, some savvy newcomers, some influential veterans like Black Lives Matter at School, Learning for Justice (formerly Teaching Tolerance), Teaching People’s History (the Zinn Education Project), the Racial Justice in Education Resource Guide (from the National Education Association), and, of course, the current star: the 1619 Project (the Pulitzer Center). To me, all these ideas seem like the ruminations of desert-island economists. They start with an impossible premise: that the students of these recommended texts actually know how to read.

I am overstating, but not by much. A significant number of American students are reading fluently and with understanding and are well on their way to becoming literate adults. But they are a minority. As of 2019, according to the National Association of Education Progress (NAEP), sometimes called the Nation’s Report Card, 35 percent of fourth-graders were reading at or above proficiency levels; that means, to spell it out, that a strong majority—65 percent, to be exact—were less than proficient. In fact, 34 percent were reading, if you can call it that, below a basic level, barely able to decipher material suitable for kids their age. Eighth-graders don’t do much better. Only 34 percent of them are proficient; 27 percent were below-basic readers. Worse, those eighth-grade numbers represent a decline from 2017 for 31 states.

As is always the case in our crazy-quilt, multiracial, multicultural country, the picture varies, depending on which kids you’re looking at. If you categorize by states, the lowest scores can be found in Alabama and New Mexico, with just 21 percent of eighth-graders reading proficiently. The best thing to say about these results is that they make the highest-scoring state—Massachusetts, with 47 percent of students proficient—look like a success story rather than the mediocrity it is.

The findings that should really push antiracist educators to rethink their pedagogical assumptions are those for the nation’s black schoolchildren. Nationwide, 52 percent of black children read below basic in fourth grade. (Hispanics, at 45 percent, and Native Americans, at 50 percent, do almost as badly, but I’ll concentrate here on black students, since antiracism clearly centers on the plight of African-Americans.) The numbers in the nation’s majority-black cities are so low that they flirt with zero. In Baltimore, where 80 percent of the student body is black, 61 percent of these students are below basic; only 9 percent of fourth-graders and 10 percent of eighth-graders are reading proficiently. (The few white fourth-graders attending Charm City’s public schools score 36 points higher than their black classmates.) Detroit, the American city with the highest percentage of black residents, has the nation’s lowest fourth-grade reading scores; only 5 percent of Detroit fourth-graders scored at or above proficient. (Cleveland’s schools, also majority black, are only a few points ahead.)

…

The tragedy for black children and their families, as well as a nation trying to reckon with racial disparities rooted in its own history, can’t be overstated. If you want to make sense of racial gaps in high school achievement, college attendance, graduation, adult income, and even incarceration, you could do worse than look at third-grade reading scores. Three-quarters of below-proficient readers in third grade remain below proficient in high school. Before third grade, children are learning to read; after that, they are reading to learn, in one well-known formulation. All future academic learning in humanities, social sciences, business, and, yes, STEM fields depends on confident, skilled reading. “The kids in the top reading group at age 8 are probably going to college. The kids in the bottom reading group probably aren’t,” as Fredrik deBoer, the iconoclastic author of The Cult of Smart, has put it. And the absence of a sheepskin is hardly the worst of it. Upward of 80 percent of adolescents in the juvenile justice system are poor readers, according to the Literacy Project Foundation. Over 70 percent of inmates in America’s prisons cannot read above a fourth-grade level. It’s been said that authorities use third-grade reading scores to predict how many prison beds will be needed. That meme is probably apocryphal, but the sad fact is that it makes sense.

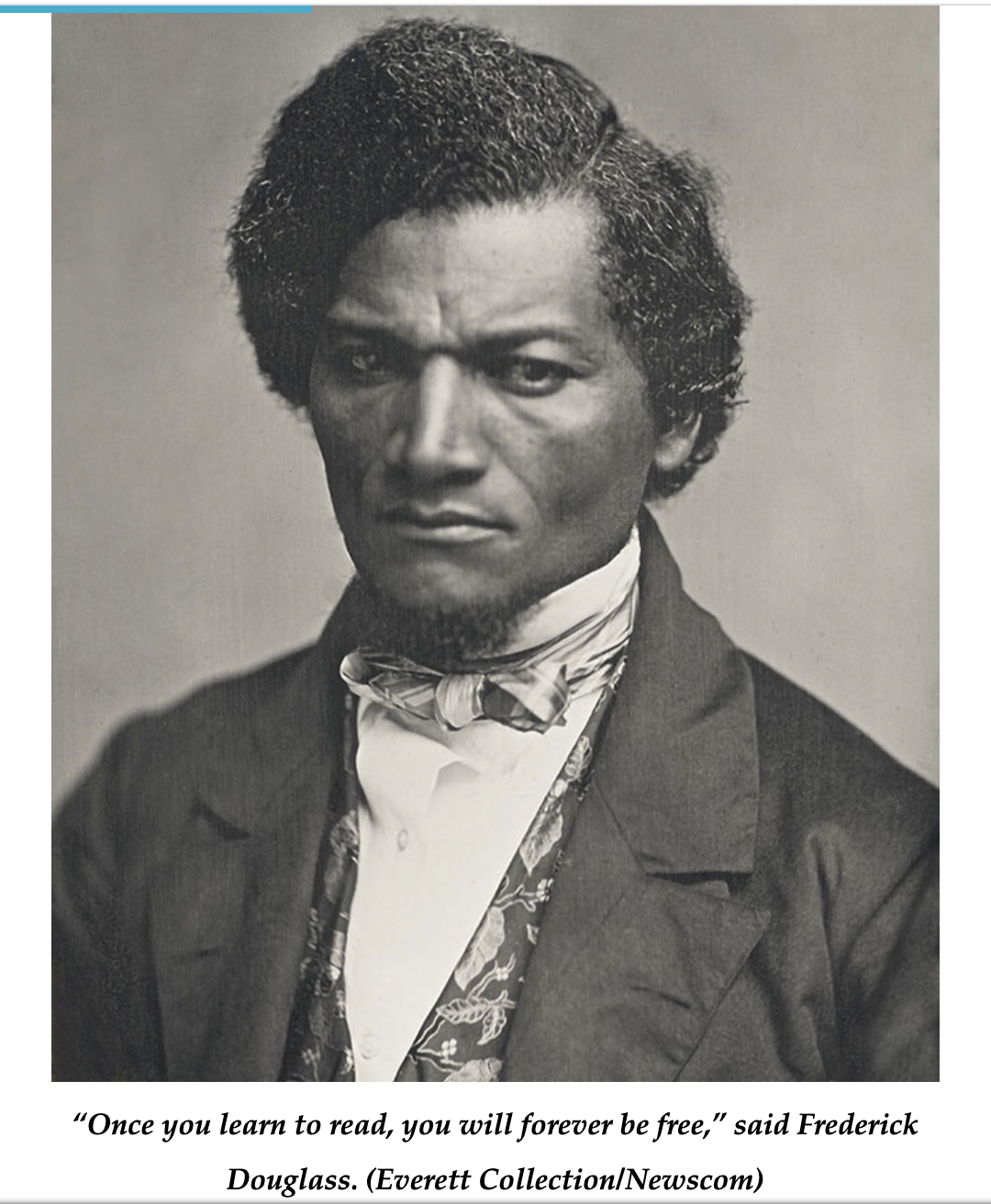

The irony would bring tears to the eyes of Martin Luther King, Jr. Before the Civil War, most Southern states had laws forbidding slaves from reading or writing. Enslaved men and women were known to risk whippings and death in order to learn their letters, sometimes with the aid of a sympathetic white but frequently on the strength of their own determination. “Once you learn to read, you will be forever free,” the most famous of those readers, Frederick Douglass, promised. What would he, or King, make of an education system that leaves more than half of twenty-first-century black kids barely literate?

….

Social-justice educators would doubtless object that the catastrophic literacy rates of black students are solid proof of the structural racism and teacher bias that they’re intent on fighting. They would rightly observe that reading scores correlate with parental income and education; black children tend to come from less affluent and less educated homes, a fact at least partially tied to historical racism. But evidence that racial disadvantage should not be an obstacle to literacy is there for anyone who bothers to look. Nearly 60 percent of black children in New York City charter schools read proficiently; that’s true for only 35 percent of those in district schools. (And 80 percent of the kids in New York City charters are economically disadvantaged.) Unless someone can prove that district teachers are more racist than those at charters—an unlikely theory—it would seem that charters simply do a better job of teaching kids to read. The differences between states also point to a pedagogical, rather than white-supremacist, explanation for racial discrepancies. People might reasonably predict that poor Southern states would have lower overall reading scores than more affluent states in the Northeast, and they’d be right. But the Urban Institute has developed a nifty interactive chart that lets us compare states adjusting for race and poverty (or other variables). The counterintuitive results show that Mississippi, the poorest state in the nation and one with a dreadful racial history and an equally dreadful education record, is turning things around. The state is now more successful at teaching disadvantaged black children to read than top-ranked and affluent Massachusetts and New Jersey.

These successes are no mystery, but they do require a quick history of the nation’s long-simmering “reading wars.” For at least a generation now, American educators’ preferred approach to reading has been known as “whole language.” Whole language encourages teachers to do “shared” and “interactive” reading with children, to sight-read words that they’ve seen before, and to guess, with the help of illustrations and intuition, when they encounter an unfamiliar word. The guiding assumption is that reading is a natural process and teachers should just guide kids toward literacy. Children don’t need direct instruction to read any more than they need instruction to learn to talk.

…..

Her conclusion: Ditch “whole language” and return to phonics

Social-justice educators would doubtless object that the catastrophic literacy rates of black students are solid proof of the structural racism and teacher bias that they’re intent on fighting. They would rightly observe that reading scores correlate with parental income and education; black children tend to come from less affluent and less educated homes, a fact at least partially tied to historical racism. But evidence that racial disadvantage should not be an obstacle to literacy is there for anyone who bothers to look. Nearly 60 percent of black children in New York City charter schools read proficiently; that’s true for only 35 percent of those in district schools. (And 80 percent of the kids in New York City charters are economically disadvantaged.) Unless someone can prove that district teachers are more racist than those at charters—an unlikely theory—it would seem that charters simply do a better job of teaching kids to read. The differences between states also point to a pedagogical, rather than white-supremacist, explanation for racial discrepancies. People might reasonably predict that poor Southern states would have lower overall reading scores than more affluent states in the Northeast, and they’d be right. But the Urban Institute has developed a nifty interactive chart that lets us compare states adjusting for race and poverty (or other variables). The counterintuitive results show that Mississippi, the poorest state in the nation and one with a dreadful racial history and an equally dreadful education record, is turning things around. The state is now more successful at teaching disadvantaged black children to read than top-ranked and affluent Massachusetts and New Jersey.

These successes are no mystery, but they do require a quick history of the nation’s long-simmering “reading wars.” For at least a generation now, American educators’ preferred approach to reading has been known as “whole language.” Whole language encourages teachers to do “shared” and “interactive” reading with children, to sight-read words that they’ve seen before, and to guess, with the help of illustrations and intuition, when they encounter an unfamiliar word. The guiding assumption is that reading is a natural process and teachers should just guide kids toward literacy. Children don’t need direct instruction to read any more than they need instruction to learn to talk.

But over recent decades, linguists, cognitive psychologists, and data-driven educators have reached a consensus that this is not what makes Johnny read. The beginning reader needs, first of all, to “de-code.” To accomplish that, teachers must systematically impart “phonemic awareness.” The shorthand for this approach is “phonics”—that is, the relation between the letters on the page and the sounds of speech. Children learn to blend those sounds, or phonemes, together into syllables, which they then combine into words. With practice, the process becomes fluent, even automatic, freeing up the bandwidth for a fuller comprehension of the meaning of the words. ….

Though whole language has been failing many millions of schoolchildren …. educators have been loath to give up their dreams. So they introduced a (supposedly) new approach with the benign-sounding name “balanced literacy.” In theory, balanced literacy blends the two methods of whole language and phonics; in practice, phonics gets short shrift. Few ed schools or teaching programs show student teachers how to teach phonics in the defined, logical progression necessary for students to catch on to the complexities of the English language. Basement-level reading scores haven’t budged.

…[T]o become proficient readers, children also must know what words mean. They will, in other words, need to develop a rich vocabulary and varied background knowledge. Finally, intelligent teaching methods are not a panacea for racial and income disparities; no matter how well black children are taught to read, white children are still more likely to grow up with educated parents, which means that they will be hearing more vocabulary words, more complex language, and more useful information about the wider world. This problem can be solved over time but only if more disadvantaged kids are given the chance to pass on the benefits of their own literacy to their children.

The reading emergency should be the primary focus for educators, especially those in a position to help black children. Yet a growing number of school districts are interviewing prospective teachers, even those for elementary school, fixated on one question: “What have you done personally or professionally to be more antiracist?” The best answer to that question would be: “Teach black children how to read.” Better yet, change the question to “What’s the best way to teach reading?” and we might see some real racial progress.

The author is quite right that reading comes much easier to those of us who grew up in a literate household. I was read to from at least 3-5 (my memory doesn’t extend to 1-2) and although I wasn’t taught to read for myself until I reached first grade, that skill came easily, and by 4th grade, after I’d exhausted the supply of books in Riverside School’s library, my mother started driving me to Greenwich Library to find adult reading material to sustain my interest. My parents were highly literate, and if one of the kids asked the meaning of word, my my father would direct us to the 12 (?) volume first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary to look it up for ourselves. We had no television in the house until I was ten, so we forced to reading (or watching it at friends’ houses — shhh!) for entertainment.

And so on; the point is, while that’s not an environment likely to be created by a single mother of 17, basic literacy can be taught to almost anyone, and a child’s natural curiosity cultivated and encouraged. Without those, a person is doomed, and the people running the educational establishment have spent the pasty fifty years enriching themselves and turning out failed, doomed children. That should be changed.