Reparations now!

/It’s no wonder that our pedagogues are so desperate to erase and rewrite history

During his show from London Monday night just hours after Queen Elizabeth II was laid to rest, CNN host Don Lemon brought up the issue of slavery and colonialism reparations during an interview with a British expert.

In the exchange, Lemon explained why some believe slavery reparations are necessary but may have been shocked about who his guest said should be paying the bill.

"You have those who are asking for reparations for colonialism and they're wondering, you know, $100 billion, $24 billion here, there, $500 million there. Some people want to be paid back and members of the public are suffering when you have all of this vast wealth. Those are legitimate concerns," Lemon said.

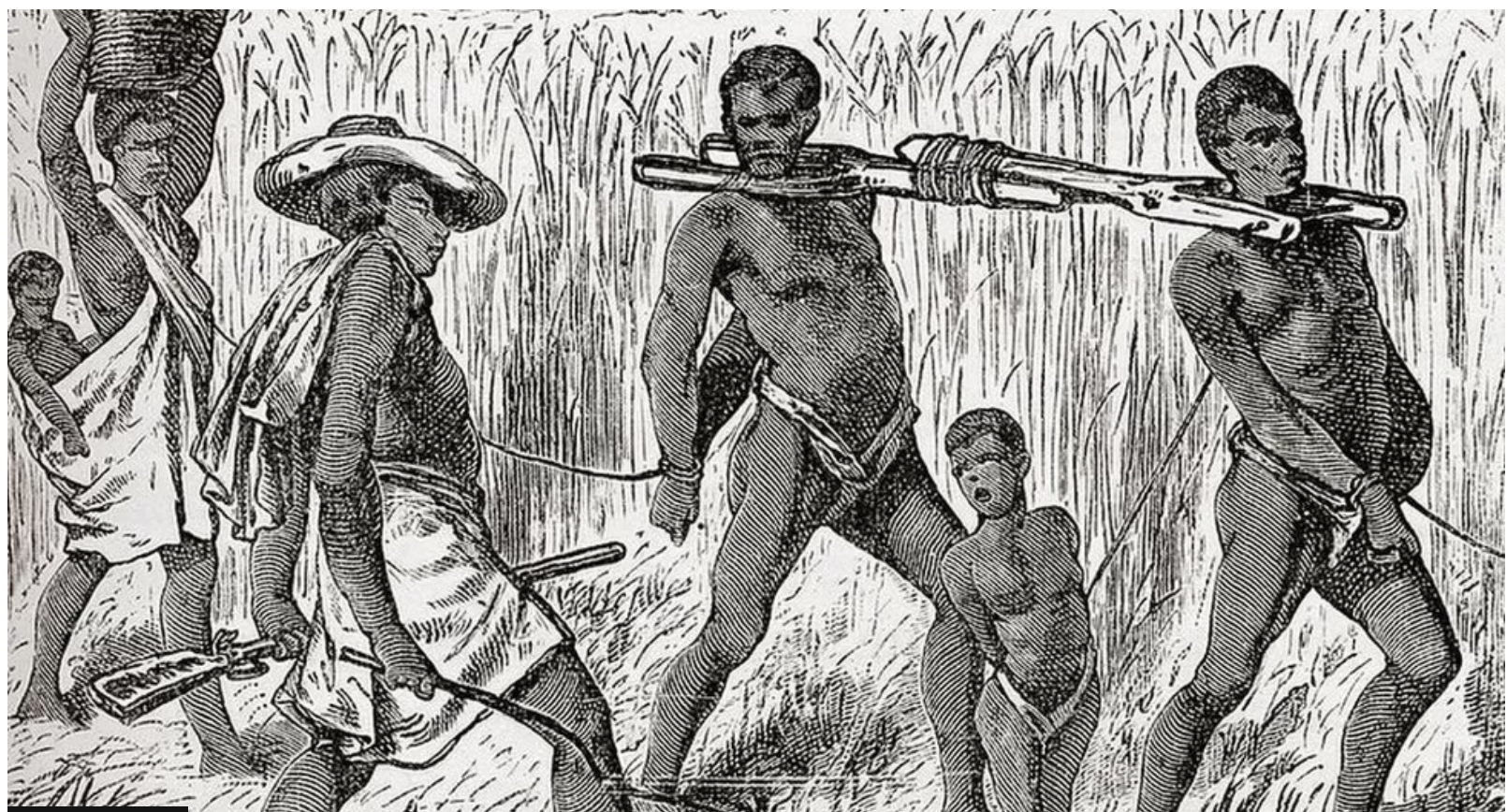

"I think you're right about reparations in terms if people want it though, what they need to do is you always need to go back to the beginning of the supply chain. Where was the beginning of the supply chain? That was in Africa," royal expert Hilary Forwich explained. "Across the entire world when slavery was taking place which was the First Nation in the world that abolished slavery? First Nation in the world to abolish it...was the British."

"Two-thousand naval men died on the high seas trying to stop slavery. Why? Because the African kings were rounding up their own people. They had them on cages waiting in the beaches. No-one was running into Africa to get them," she continued. "I think you're totally right. If reparations need to be paid we need to go right back to the beginning of that supply chain and say, who was rounding up their own people and having them hang from cages. Absolutely, that's where they should start. And maybe, I don't know, the descendants of those families where they died in the high seas trying to stop the slavery, those families should receive something soon."

OOPS!

But wait, there’s more!

From BBC:

My great-grandfather, Nwaubani Ogogo Oriaku, was what I prefer to call a businessman, from the Igbo ethnic group of south-eastern Nigeria. He dealt in a number of goods, including tobacco and palm produce. He also sold human beings.

"He had agents who captured slaves from different places and brought them to him," my father told me.

Nwaubani Ogogo's slaves were sold through the ports of Calabar and Bonny in the south of what is today known as Nigeria.

People from ethnic groups along the coast, such as the Efik and Ijaw, usually acted as stevedores for the white merchants and as middlemen for Igbo traders like my great-grandfather.

They loaded and offloaded ships and supplied the foreigners with food and other provisions. They negotiated prices for slaves from the hinterlands, then collected royalties from both the sellers and buyers.

The only life they knew

Nwaubani Ogogo lived in a time when the fittest survived and the bravest excelled. The concept of "all men are created equal" was completely alien to traditional religion and law in his society.

[Hmm. Where did that concept come from?

It would be unfair to judge a 19th Century man by 21st Century principles.

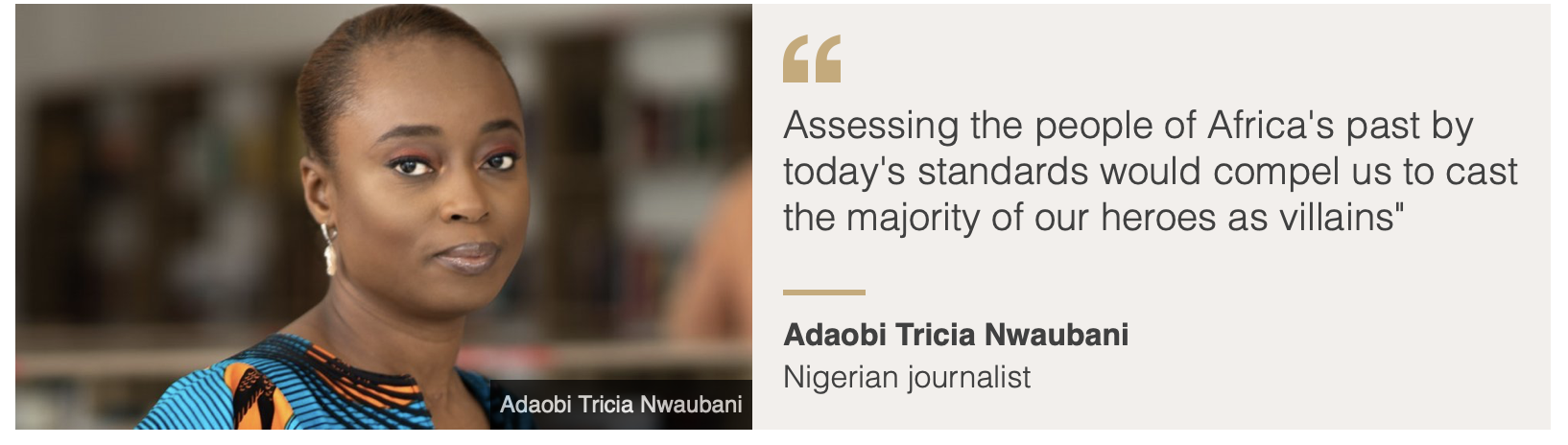

Assessing the people of Africa's past by today's standards would compel us to cast the majority of our heroes as villains, denying us the right to fully celebrate anyone who was not influenced by Western ideology.

Igbo slave traders like my great-grandfather did not suffer any crisis of social acceptance or legality. They did not need any religious or scientific justifications for their actions. They were simply living the life into which they were raised.

That was all they knew.

The slaves were being transported by middlemen, along with a consignment of tobacco and palm produce, from Nwaubani Ogogo's hometown of Umuahia to the coast.

Buying and selling of human beings among the Igbo had been going on long before the Europeans arrived. People became slaves as punishment for crime, payment for debts, or prisoners of war.

The successful sale of adults was considered an exploit for which a man was hailed by praise singers, akin to exploits in wrestling, war, or in hunting animals like the lion.

Igbo slaves served as domestic servants and labourers. They were sometimes also sacrificed in religious ceremonies and buried alive with their masters to attend to them in the next world.

When the British extended their rule to south-eastern Nigeria in the late 19th Century and early 20th Century, they began to enforce abolition through military action.

But by using force rather than persuasion, many local people such as my great-grandfather may not have understood that abolition was about the dignity of humankind and not a mere change in economic policy that affected demand and supply.

"We think this trade must go on," one local king in Bonny infamously said in the 19th Century.

"That is the verdict of our oracle and our priests. They say that your country, however great, can never stop a trade ordained by God."

Slave trade in the 20th Century

Acclaimed Igbo historian Adiele Afigbo described the slave trade in south-eastern Nigeria which lasted until the late 1940s and early 1950s as one of the best kept secrets of the British colonial administration.

While the international trade ended, the local trade continued.

"The government was aware of the fact that the coastal chiefs and the major coastal traders had continued to buy slaves from the interior," wrote Afigbo in The Abolition of the Slave Trade in Southern Nigeria: 1885 to 1950.

…

Records from the UK's National Archives at Kew Gardens show how desperately the British struggled to end the internal trade in slaves for almost the entire duration of the colonial period.

They promoted legitimate trade, especially in palm produce. They introduced English currency to replace the cumbersome brass rods and cowries that merchants needed slaves to carry. They prosecuted offenders with prison sentences.

"By the 1930s, the colonial establishment had been worn down," wrote Afigbo.

"As a result, they had come to place their hope for the extirpation of the trade on the corrosive effect over time of education and general civilisation."