Muttonheads

/California, 2023

California’s food recycling law gets smacked in the face by reality

CHICO, Calif., April 8 (Reuters) — A California law requiring grocery stores and restaurants to donate leftover food has been hard for local food banks and small towns to implement due to climbing fuel costs and uncertainty over who pays for food recovery.

The California law, which took effect in January, mandates that national retailers such as Amazon.com Inc (AMZN.O) and Kroger (KR.N) as well as small grocery and convenience stores, donate unsold food, redirecting anything edible from landfills and composting anything inedible. It tasks cities and counties with formulating local plans, with a statewide goal of recovering 20% of edible food by 2025.

Implementing the new rules has been especially challenging in rural California. As the North State Food Bank prepared for an influx of newly-mandated donations, the daunting costs of picking up food across 8,000 square miles (5 million acres/20,720 square kilometers) in six northern California counties became clear.

"I can't send the truck all over town, picking up leftover sandwiches," said Tom Dearmore, director of community services at the Butte County Community Action Agency, which houses the food bank.

And it’s not just the high cost of driving around the countryside picking up uneaten sandwiches that’s causing troubles here:

Most food banks will buy in bulk for suppliers rather than depend on random donations from pretty much anyone in varying amounts, in pretty much any condition. Processing such donations, having to inspect each and every one for edibility and expiration date without knowing much about the sourcing, or the storage, or the potential insect infestation risk, after all, is pretty labor-intensive. It's more efficient for the food banks to buy in bulk and have the quality control in place right there — and they can serve more people that way, too.

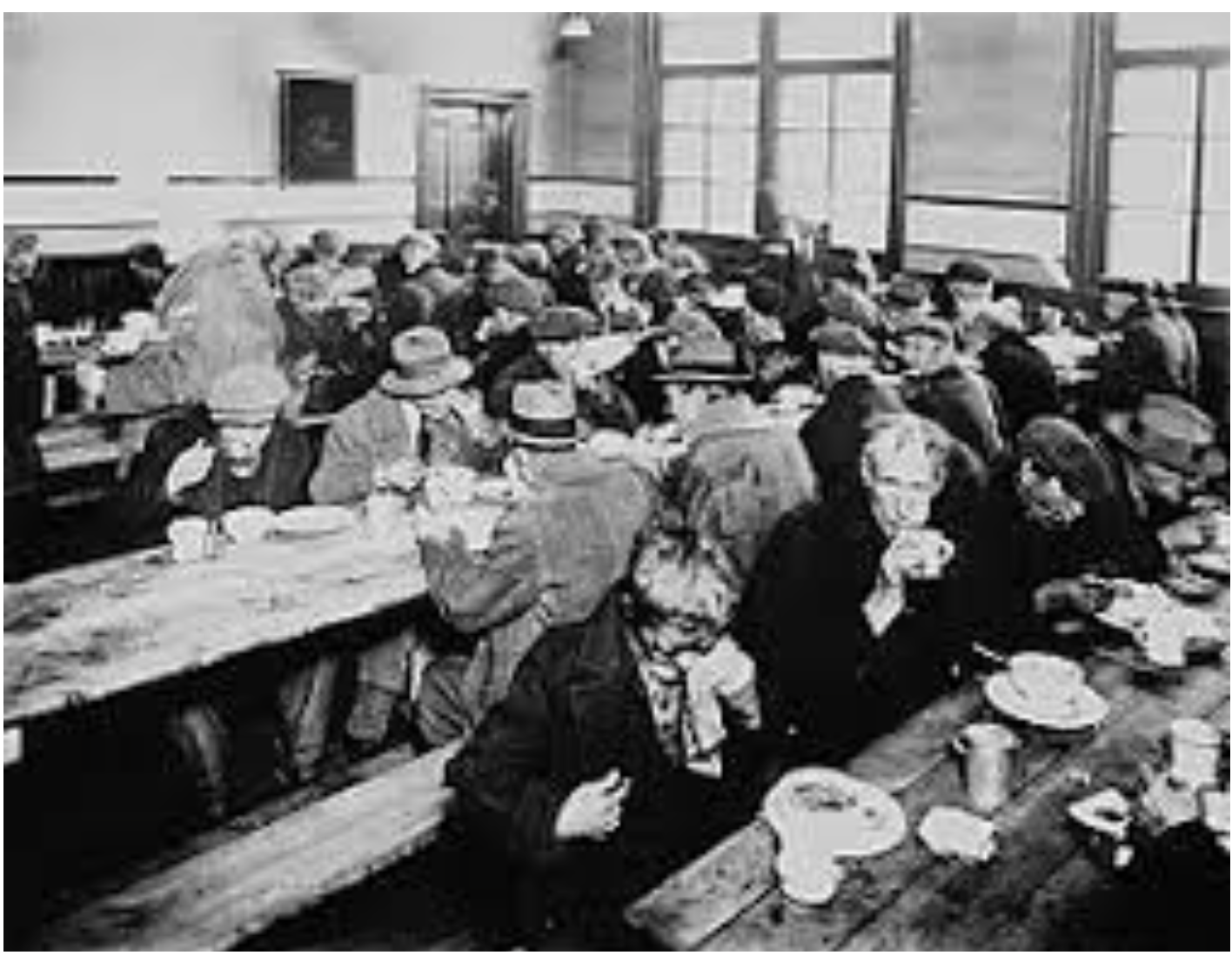

I doubt a single one of the California legislators who foisted this on their constituents has ever volunteered in a soup kitchen or food bank. I have — and did so for three years, and there is no possible use for odd-lots of vegetable or pork chops when you’re preparing meals for 300 people three times a day.

What is there to do, other than compost it, with 3-day-old vegetables diverted from a restaurant’s dumpster, or meat prepared but uncooked, or loose boxes of hamburger that might or might not have sat outside the refrigerator for a day — the donee has no way of knowing — why take the risk of poisoning the clientele? We would gladly accept food from, say, the large grocery chains because we knew its provenance, but a truck showing up at the door with a miscellaneous load of foodstuffs collected from a dozen different, unknown sources? I don’t think so.

There’s no reason why the desire to do good has to shut down the brain, but it seems to do exactly that when Progressives are involved. Of course, the other explanation for this separation of heart and mind is that all that blood draining from the Progressives’ hearts left them brain dead years ago.

That seems more likely.